История

Велосипед принцессы Дианы и другие предметы были проданы сегодня на аукционе в Оксфордшире. Голубой велосипед 1970-х годов Ladies Raleigh Traveler регулярно

Лидер лейбористов Джереми Корбин встречался с период "холодной войны" с советским шпионом, которому он рассказывал о том, что "его действия блокирует MI5".

По инициативе Фонда еврейского наследия Великобритании впервые составлена карта 3 318 синагог Европы

На прошлой неделе на сайте Фонда еврейского наследия Великобритании опубликована подробная карта синагог Европы, составленная специалистами в области иудаики

Британское правительство выделит в этом году 144 000 фунтов стерлингов на борьбу с антисемитизмом в студенческих кампусах. Об этом сегодня заявил секретарь по

Ученые Кембриджского университета решили заняться проблемой культуры употребления спиртных напитков в Великобритании. В ходе своего расследования они сравнивали

Лейбористская партия страдает демонизацией сионизма. Об этом заявили три ведущих еврейских историка Великобритании, которые на этой неделе написали открытое письмо

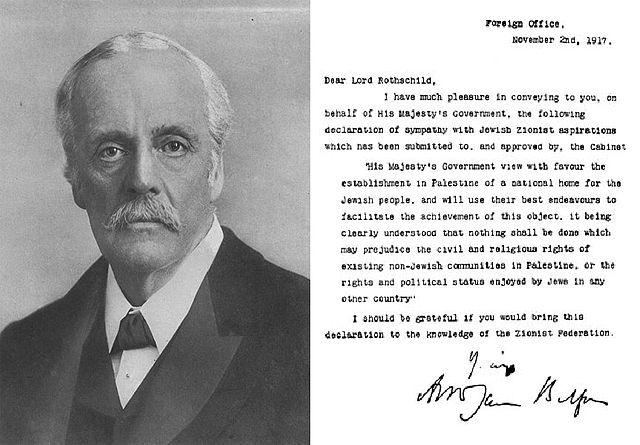

В преддверии 100-летия Декларации Бальфура, в Великобритании был проведен опрос общественного мнения по поводу отношения британцев к данному документу, а также к

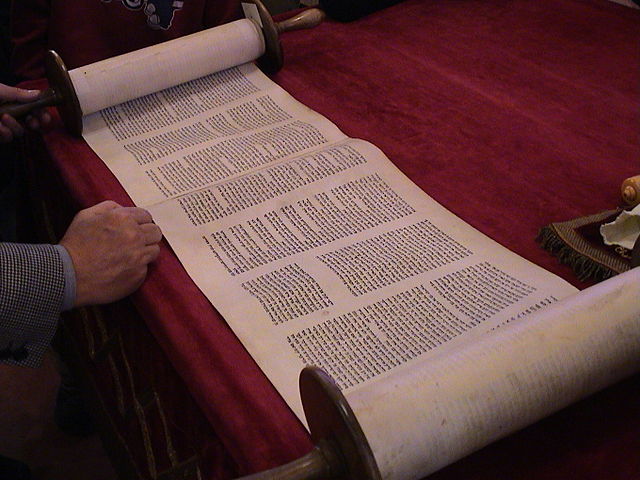

Спустя 75 лет Свиток Торы из синагоги Оломоуца в Чехии вернулся на родину из Великобритании. Пенсионер Питер Брайс, который вернул реликвию на место спустя многие

Фасад известного кошерного мясного магазина в Ливерпуле, являющегося частью исторического наследия Великобритании, будет демонтирован и аккуратно перенесён в Музей Ливерпуля благодаря гранту в размере 300 000 фунтов, выделенному на этот проект Лотерейным фондом Великобритании. Магазин P Galkoff открылся в 1907 году в Пембрук-Плейс, недалеко от центра Ливерпуля, и был перестроен в стиле ар-деко в 1930-е годы. Данное здание, начиная с 1820-х годов, использовалось под самые разные учреждения. По словам куратора организации “Национальные музеи Ливерпуля” Поппи Лирман, расцвет еврейского магазина пришёлся на период 1934-1965 годов, когда еврейское население города составляло 7500 человек, что почти в 4 раза больше, нежели сегодня.

Исследовательской группе из университетов Оксфорда, Эдинбурга и Университетского колледжа Корка помогали ученые-граждане со всей Англии, Уэльса, Северной Ирландии, Шотландии и Ирландии. Финансируемые Исследовательским советом по искусству и гуманитарным наукам (Arts and Humanities Research Council, AHRC), они провели последние пять лет в поисках и записях информации обо всех городищах Великобритании и Ирландии. В общей сложности команда насчитала 4 147 городищ, и собрала детальную информацию о каждом из них на веб-сайте, который будет доступен для публики, и при этом полностью бесплатный (фото-wikimedia).

Редакция

Образование

-

Оксфордский университет возглавил рейтинг вузов Великобритании по 10 предметам

Оксфордский университет снова закрепил свой статус мирового академического лидера, будучи названным лучшим...Подробнее...

Оксфордский университет возглавил рейтинг вузов Великобритании по 10 предметам

Оксфордский университет снова закрепил свой статус мирового академического лидера, будучи названным лучшим...Подробнее... -

Бесплатное школьное питание будет предоставлено еще для 500 000 детей

Правительство на этой неделе заявило, что любой ребенок в Англии, родители которого получают универсальный кредит,...Подробнее...

Бесплатное школьное питание будет предоставлено еще для 500 000 детей

Правительство на этой неделе заявило, что любой ребенок в Англии, родители которого получают универсальный кредит,...Подробнее... -

Новый отчет приоткрывает завесу над проблемой антисемитизма в университетах Великобритании

В новом отчете подчеркивается рост антисемитизма и страха среди еврейских студентов в Великобритании. 36-страничный...Подробнее...

Новый отчет приоткрывает завесу над проблемой антисемитизма в университетах Великобритании

В новом отчете подчеркивается рост антисемитизма и страха среди еврейских студентов в Великобритании. 36-страничный...Подробнее... -

Оксфордский университет занял первое место в Великобритании по инвестициям в ремонт зданий

Согласно новому национальному исследованию, Оксфордский университет возглавил национальный рейтинг по инвестициям...Подробнее...

Оксфордский университет занял первое место в Великобритании по инвестициям в ремонт зданий

Согласно новому национальному исследованию, Оксфордский университет возглавил национальный рейтинг по инвестициям...Подробнее... -

Компания из Абу-Даби приобрела долю в британском частном школьном операторе Nord Anglia Education за $600 млн.

17 апреля Mubadala Investment Company из Абу-Даби объявила о приобретении миноритарной доли в британском частном школьном...Подробнее...

Компания из Абу-Даби приобрела долю в британском частном школьном операторе Nord Anglia Education за $600 млн.

17 апреля Mubadala Investment Company из Абу-Даби объявила о приобретении миноритарной доли в британском частном школьном...Подробнее... -

Шотландская школа-интернат будет принимать оплату в биткоинах

Шотландская школа-интернат объявила, что будет принимать оплату за обучение в криптовалюте биткоин. Lomond School...Подробнее...

Шотландская школа-интернат будет принимать оплату в биткоинах

Шотландская школа-интернат объявила, что будет принимать оплату за обучение в криптовалюте биткоин. Lomond School...Подробнее... -

МВД Великобритании предупредило руководство LSE о возможных последствиях оправдания действий ХАМАСа

МВД Великобритании предупредило руководство Лондонской школы экономики (LSE) перед предстоящей презентацией...Подробнее...

МВД Великобритании предупредило руководство LSE о возможных последствиях оправдания действий ХАМАСа

МВД Великобритании предупредило руководство Лондонской школы экономики (LSE) перед предстоящей презентацией...Подробнее... -

Число учеников в еврейских школах Соединенного Королевства сократилось впервые за три десятилетия

Число учеников в еврейских школах Соединенного Королевства сократилось впервые за три десятилетия. Об этом...Подробнее...

Число учеников в еврейских школах Соединенного Королевства сократилось впервые за три десятилетия

Число учеников в еврейских школах Соединенного Королевства сократилось впервые за три десятилетия. Об этом...Подробнее... -

Лорд Хейг вступил в должность канцлера Оксфордского университета

Лорд Хейг официально стал 160-м канцлером Оксфордского университета на церемонии, которая состоялась сегодня...Подробнее...

Лорд Хейг вступил в должность канцлера Оксфордского университета

Лорд Хейг официально стал 160-м канцлером Оксфордского университета на церемонии, которая состоялась сегодня...Подробнее... -

Британские чиновники предупредили родителей о штрафах до £ 2500 за прогулы учеников

Родителей учеников британских школ предупредили о том, что им могут грозить штрафы в размере до 2500 фунтов стерлингов...Подробнее...

Британские чиновники предупредили родителей о штрафах до £ 2500 за прогулы учеников

Родителей учеников британских школ предупредили о том, что им могут грозить штрафы в размере до 2500 фунтов стерлингов...Подробнее...

Традиции

Рождество, Ханука и как выжить в праздничном хаосе?

Рождество, Ханука и как выжить в праздничном хаосе?

Рождество, Ханука и как выжить в праздничном хаосе?

Празднование Хануки в старейшем здании Вестминстера станет ежегодным мероприятием

Празднование Хануки в старейшем здании Вестминстера станет ежегодным мероприятием

Празднование Хануки в старейшем здании Вестминстера станет ежегодным мероприятием

Стало известно, сколько было потрачено на коронацию Короля Чарльза и Королевы-консорт Камиллы

Стало известно, сколько было потрачено на коронацию Короля Чарльза и Королевы-консорт Камиллы

Стало известно, сколько было потрачено на коронацию Короля Чарльза и Королевы-консорт Камиллы

Король Чарльз и Королева-консорт Камилла устроили ежегодный дипломатический прием в Букингемском дворце

Король Чарльз и Королева-консорт Камилла устроили ежегодный дипломатический прием в Букингемском дворце

Король Чарльз и Королева-консорт Камилла устроили ежегодный дипломатический прием в Букингемском дворце

Еврейские традиции, которые Стармер может привнести на Даунинг-стрит

Еврейские традиции, которые Стармер может привнести на Даунинг-стрит

Еврейские традиции, которые Стармер может привнести на Даунинг-стрит

Король Чарльз и принц Эндрю «воюют» из-за особняка Royal Lodge

Король Чарльз и принц Эндрю «воюют» из-за особняка Royal Lodge

Король Чарльз и принц Эндрю «воюют» из-за особняка Royal Lodge

Королева-консорт Камилла больше не будет покупать изделия из натурального меха

Королева-консорт Камилла больше не будет покупать изделия из натурального меха

Королева-консорт Камилла больше не будет покупать изделия из натурального меха

Король Чарльз стал покровителем The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews

Король Чарльз стал покровителем The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews

Король Чарльз стал покровителем The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews

Несмотря на преклонный возраст герцог Эдвард Кентский продолжает исполнять обязанности члена Королевской семьи

Несмотря на преклонный возраст герцог Эдвард Кентский продолжает исполнять обязанности члена Королевской семьи

Несмотря на преклонный возраст герцог Эдвард Кентский продолжает исполнять обязанности члена Королевской семьи

Эксперты обсуждают решение короля Чарльза открыть для публики Букингемский дворец и Балморал

Эксперты обсуждают решение короля Чарльза открыть для публики Букингемский дворец и Балморал

Эксперты обсуждают решение короля Чарльза открыть для публики Букингемский дворец и Балморал

Спорт

-

Все 20 футбольных клубов Премьер-лиги приняли участие в семинарах по антисемитизму

Как сообщило издание Jewish News, каждый футбольный клуб Премьер-лиги принял участие в семинарах, посвященных росту...Подробнее...

Все 20 футбольных клубов Премьер-лиги приняли участие в семинарах по антисемитизму

Как сообщило издание Jewish News, каждый футбольный клуб Премьер-лиги принял участие в семинарах, посвященных росту...Подробнее... -

Руководство футбольного клуба Manchester City объявило о рекордном доходе в размере £ 715 млн.

Руководство футбольного клуба Manchester City объявило о рекордном доходе в ходе выступления в Премьер-лиге в размере...Подробнее...

Руководство футбольного клуба Manchester City объявило о рекордном доходе в размере £ 715 млн.

Руководство футбольного клуба Manchester City объявило о рекордном доходе в ходе выступления в Премьер-лиге в размере...Подробнее... -

Пеп Гвардиола подписал новый двухлетний контракт с Manchester City

Пеп Гвардиола — один из самых успешных футбольных менеджеров в истории, выигравший 39 трофеев за время работы...Подробнее...

Пеп Гвардиола подписал новый двухлетний контракт с Manchester City

Пеп Гвардиола — один из самых успешных футбольных менеджеров в истории, выигравший 39 трофеев за время работы...Подробнее... -

Студенты оксфордского Ориэл колледжа завоевали две золотые медали на Парижской Олимпиаде

Ориэл колледж впервые в своей истории стал свидетелем того, как двое его студентов выиграли медали на одной...Подробнее...

Студенты оксфордского Ориэл колледжа завоевали две золотые медали на Парижской Олимпиаде

Ориэл колледж впервые в своей истории стал свидетелем того, как двое его студентов выиграли медали на одной...Подробнее... -

Более полумиллиона билетов на соревнования, которые будут проходить в рамках Олимпийских игр в Париже, до сих пор не проданы

Более полумиллиона билетов на соревнования, которые будут проходить в рамках Олимпийских игр в Париже, до сих...Подробнее...

Более полумиллиона билетов на соревнования, которые будут проходить в рамках Олимпийских игр в Париже, до сих пор не проданы

Более полумиллиона билетов на соревнования, которые будут проходить в рамках Олимпийских игр в Париже, до сих...Подробнее...